Submitted by Jennifer RewolinskiDr. Deborah Williamson is an Associate Professor in the College of Nursing at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC), Charleston. Dr. Williamson, Community Health Maps (CHM) and MUSC have partnered in providing training that integrates GIS and CHM tools for a high school Teen Health Leadership Program. Dr. Williamson has worked with both community members and students. Dr. Williamson believes that, “GIS has the potential to substantially increase community engagement and is truly a concept of the neighborhood taking control of their data.” She notes that while researchers might study a community, that a community’s input is essential to understanding the cultural and environmental context surrounding health issues: “GIS mapping puts the community members on more of a level playing field with their research partners.” GIS can empower and educate community members to identify their key issues, to become a part of an analysis, and to provide solutions. When communities are given the opportunity to map their own health, discovery, and awareness, positive changes can result. When a community feels it has more of a say through engagement with GIS, or communication with a map, intervention is more likely to be effective.For the past three semesters, Dr. Williamson has used GIS in her own classroom as a capstone project for population health students. They, “find it fun and can take it with them into other settings, it fits into the world of new technology, and it takes people to the next step of looking at health issues.” Mapping offers a different way to help students visualize Social Determinants of Health and to make the connection between what population health is, and the factors that promote or deter it.

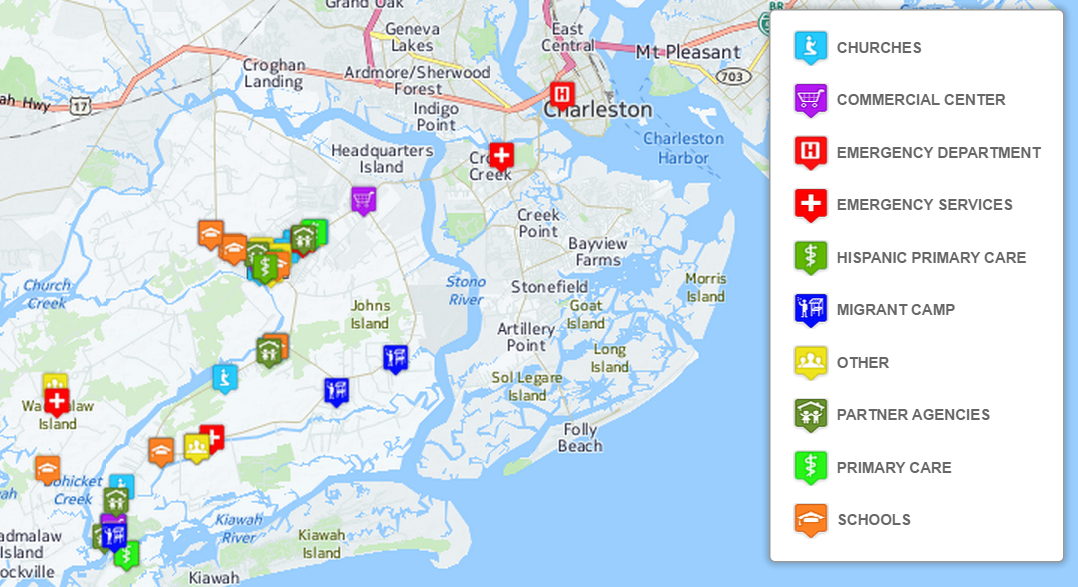

Dr. Williamson believes that, “GIS has the potential to substantially increase community engagement and is truly a concept of the neighborhood taking control of their data.” She notes that while researchers might study a community, that a community’s input is essential to understanding the cultural and environmental context surrounding health issues: “GIS mapping puts the community members on more of a level playing field with their research partners.” GIS can empower and educate community members to identify their key issues, to become a part of an analysis, and to provide solutions. When communities are given the opportunity to map their own health, discovery, and awareness, positive changes can result. When a community feels it has more of a say through engagement with GIS, or communication with a map, intervention is more likely to be effective.For the past three semesters, Dr. Williamson has used GIS in her own classroom as a capstone project for population health students. They, “find it fun and can take it with them into other settings, it fits into the world of new technology, and it takes people to the next step of looking at health issues.” Mapping offers a different way to help students visualize Social Determinants of Health and to make the connection between what population health is, and the factors that promote or deter it. Finally, Dr. Williamson sees GIS as bi-directional: it supports visualizing gaps and assets while also providing the ability to disseminate and build on information via intervention programs to improve health outcomes and strengthen communities. GIS is also broadly applicable to almost any discipline and easily used by those with little expertise. “Presenting raw data to a community or students doesn’t mean a lot,” Dr. Williamson comments, “but when that same data is aggregated visually it instantly communicates a message to any audience.” GIS is clearly suitable as an effective educational tool in the classroom and in communities.CHM thanks Dr. Williamson for her continued collaboration and time spent advancing the CHM program through use of the CHM tools at MUSC. CHM values our partnership with MUSC and hope that the future is as mutually beneficial as the past few years.Field data collection for the CHM workflow bridges the divide between learning in a classroom and experiencing conditions in a community. For the capstone project, students use CHM labs and parts of the CHM workflow, including phone data collection with iForm or Fulcrum, integration of the data into QGIS, and presenting the data with Carto or Google Maps. Dr. Williamson’s students often upload their data from iForm to Google Maps because of its familiarity and easy access.One student project involved identifying migrant camps as a community in need, and assessing the community through surveys and key informant interviews. When the data showed that migrant workers often lack knowledge of health information and access to healthcare services, students mapped locations of migrant camps near Charleston, SC in relation to urgent care facilities and shared the data with the migrant outreach workers from a local community health center. Later, an intervention was developed to provide hands on CPR and first aid instruction to 60 workers. This project displays successful application of CHM tools in an educational and community context resulting in an intervention that may offer real change.

Finally, Dr. Williamson sees GIS as bi-directional: it supports visualizing gaps and assets while also providing the ability to disseminate and build on information via intervention programs to improve health outcomes and strengthen communities. GIS is also broadly applicable to almost any discipline and easily used by those with little expertise. “Presenting raw data to a community or students doesn’t mean a lot,” Dr. Williamson comments, “but when that same data is aggregated visually it instantly communicates a message to any audience.” GIS is clearly suitable as an effective educational tool in the classroom and in communities.CHM thanks Dr. Williamson for her continued collaboration and time spent advancing the CHM program through use of the CHM tools at MUSC. CHM values our partnership with MUSC and hope that the future is as mutually beneficial as the past few years.Field data collection for the CHM workflow bridges the divide between learning in a classroom and experiencing conditions in a community. For the capstone project, students use CHM labs and parts of the CHM workflow, including phone data collection with iForm or Fulcrum, integration of the data into QGIS, and presenting the data with Carto or Google Maps. Dr. Williamson’s students often upload their data from iForm to Google Maps because of its familiarity and easy access.One student project involved identifying migrant camps as a community in need, and assessing the community through surveys and key informant interviews. When the data showed that migrant workers often lack knowledge of health information and access to healthcare services, students mapped locations of migrant camps near Charleston, SC in relation to urgent care facilities and shared the data with the migrant outreach workers from a local community health center. Later, an intervention was developed to provide hands on CPR and first aid instruction to 60 workers. This project displays successful application of CHM tools in an educational and community context resulting in an intervention that may offer real change.

Wildly Successful Community Health Mapping Workshops at MUSC!

Community Health Maps (CHM) conducted it's largest and most successful workshops ever at the end of September at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). The training at MUSC was divided into three workshops and a presentation. The attendees were a mix of professors, students and researchers, most of whom had little to no experience with GIS. Despite this fact, nearly everyone was able to collect data and make a map. This is a testament to the easy to use nature of the CHM workflow.It began Monday morning with the first workshop. This was an Intermediate Session for those Community Health Mappers who had been working on projects since the April CHM workshop. We spent two hours covering more advanced topics and answering project specific questions. Following that, Kurt Menke presented a CHM project overview at a brown bag lunch session to 30 attendees. Matt Jones closed this session with a 10 minute talk detailing how he used The Community Health Maps workflow this summer to map access to care on Johns Island.The second workshop was Monday afternoon. It was a two hour session covering field data collection with iForm, and mapping that data online with CartoDB. There were 55 attendees at this session, the vast majority of whom had no GIS experience. In just two hours all 55 attendees were able to collect field data and make a map in CartoDB!

Following that, Kurt Menke presented a CHM project overview at a brown bag lunch session to 30 attendees. Matt Jones closed this session with a 10 minute talk detailing how he used The Community Health Maps workflow this summer to map access to care on Johns Island.The second workshop was Monday afternoon. It was a two hour session covering field data collection with iForm, and mapping that data online with CartoDB. There were 55 attendees at this session, the vast majority of whom had no GIS experience. In just two hours all 55 attendees were able to collect field data and make a map in CartoDB! The final workshop on Tuesday was a 5 hour session covering the use of QGIS. The workshop consisted of a custom Charleston based QGIS exercise. Each of the 35 participants worked with a set of Charleston GIS data while learning the basic layout of QGIS. They learned how to add data, style it, and compose a map. The workshop ended with a discussion of each participants goals and project specific questions.

The final workshop on Tuesday was a 5 hour session covering the use of QGIS. The workshop consisted of a custom Charleston based QGIS exercise. Each of the 35 participants worked with a set of Charleston GIS data while learning the basic layout of QGIS. They learned how to add data, style it, and compose a map. The workshop ended with a discussion of each participants goals and project specific questions. In total almost 80 people attended one or more sections of the training! Thanks go out to Dr. Deborah Williamson for hosting the workshops, Dana Burshell for organizing the entire event and assisting during the workshops, and to Sarah Reynolds who was invaluable in providing Mac and QGIS support!

In total almost 80 people attended one or more sections of the training! Thanks go out to Dr. Deborah Williamson for hosting the workshops, Dana Burshell for organizing the entire event and assisting during the workshops, and to Sarah Reynolds who was invaluable in providing Mac and QGIS support!

Teens Map Environmental Health of Their Community (Sea Islands, South Carolina)

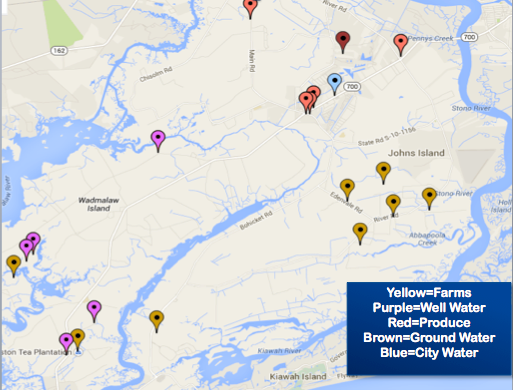

By Guest Blogger: Derek Toth - Communities in Schools CharlestonThe Teen Health Leadership Program (THLP) is in their eight year of existence at St. John’s High School on Johns Island. The program gathers leaders of the school together and focuses on a health topic they feel is affecting their community and assists the community in understanding this topic through the use of media dissemination. In the past, topics included Autism, Cancer, Stress, Obesity and Alcohol and Drugs and This year, the students wanted to look at their community as a whole with a topic of Environmental Health.The THLP students wanted to see what makes their Sea Island community different. The Sea Islands are composed of John’s Island, Wadmalaw Island, Seabrook Island and Kiawah Island outside of Charleston, South Carolina. Students primarily come from John’s and Wadmalaw Islands. These islands are extremely different for many reasons. The students wanted to be able to translate these differences in a new form for the Teen Health Leadership Program. The students were presented with an opportunity to use the Community Health Mapping tools discussed on this blog, and some training made available from the National Library of Medicine. With GIS, the students can pin point differences within the islands for their community to see.(This January Kurt Menke conducted a Community Health Map training at the Medical University of South Carolina College of Nursing. Two teachers with Communities in Schools Charleston attended and the next afternoon Kurt Menke went to St. John's High School and showed the students how to map their campus with their iPhones.)  The students used smart phones, along with an app named iForm, to map points of interest with GPS. They collected well water locations, ground and city water sources, as well as, places in the community to purchase food. The food resources they mapped included farmers markets, produce stands, grocery stores and local farms. The students were able to indicate these points on a map. Google maps was used to create the final map.With the final map they were able to determine that people on Wadmalaw Island have less access to food and water than those on St. John's Island. For example, Wadmalaw Island is limited in places to buy produce or groceries, and has limited access to the farms that John’s Island has. Residents of Wadmalaw Island are on well water, and obtain their produce at the local grocery store on Johns Island, as opposed to driving to one of the many local farms.

The students used smart phones, along with an app named iForm, to map points of interest with GPS. They collected well water locations, ground and city water sources, as well as, places in the community to purchase food. The food resources they mapped included farmers markets, produce stands, grocery stores and local farms. The students were able to indicate these points on a map. Google maps was used to create the final map.With the final map they were able to determine that people on Wadmalaw Island have less access to food and water than those on St. John's Island. For example, Wadmalaw Island is limited in places to buy produce or groceries, and has limited access to the farms that John’s Island has. Residents of Wadmalaw Island are on well water, and obtain their produce at the local grocery store on Johns Island, as opposed to driving to one of the many local farms. The final map was inserted into the Environmental Health project for the community to have a unique perspective of their Sea Island Community. Overall, the students felt that using their smart phones to map their community was easy to learn and fun. They were able to grasp the information quickly and seemed pleased with their results. The group feels it reached it’s goal of accomplishing a fresh look at the Sea Islands and felt it added to their presentation on Environmental Health.

The final map was inserted into the Environmental Health project for the community to have a unique perspective of their Sea Island Community. Overall, the students felt that using their smart phones to map their community was easy to learn and fun. They were able to grasp the information quickly and seemed pleased with their results. The group feels it reached it’s goal of accomplishing a fresh look at the Sea Islands and felt it added to their presentation on Environmental Health.